Sophie Williams writes on the politics behind a deadly virus that has infected thousands. Sophie is a medical student and health activist based in London

The outbreak

The current outbreak of Ebola in West Africa has infected and killed more people since its start in December than any previous outbreak. There have been more than 2,250 cases, as compared to 450 in 2000. Médecins Sans Frontières are reporting it probably won’t be brought under control until autumn. Schools across Nigeria are set to remain closed until 13 October to prevent any further spread of the infection.

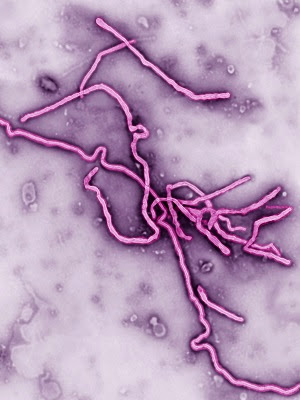

The Ebola virus works by hijacking the body’s immune system. It infects the cells that would normally detect and override the virus, turning the body’s defence systems against itself.

The Ebola virus works by hijacking the body’s immune system. It infects the cells that would normally detect and override the virus, turning the body’s defence systems against itself.

Ebola causes blood to clot inside blood vessels and organs, as well as damaging the vessels themselves. This causes one common sign of Ebola infection: bleeding from eyes, mouth and other orifices.

The virus spreads through contact with bodily fluids (which makes it less contagious than diseases transmitted through the air such as flu). It’s thought that most outbreaks begin through consumption of infected bush meat, but the infection spreads fastest after infected people become very ill or die.

There is no cure or vaccine currently available for Ebola. The main treatments are “supportive” – they help the body to fight the infection without doing anything to specifically target the virus itself. These include providing intravenous fluids to maintain normal levels of body salts, maintaining oxygen provision and blood pressure, and treating other infections should they occur.

The treatments

British nurse William Pooley was flown back to Britain from Sierra Leone last week after contracting Ebola from patients he was treating. Pooley is one of four international patients receiving experimental drugs to combat the disease.

This has been made possible by an unprecedented decision by the World Health Organisation to permit the use of “unproven interventions” for people suffering from Ebola.

This has been made possible by an unprecedented decision by the World Health Organisation to permit the use of “unproven interventions” for people suffering from Ebola.

However, there are experimental treatments that have a reasonable chance of working – and those that don’t. Two US aid workers have recovered from Ebola while taking ZMapp, an experimental drug containing a mixture of antibodies. It has shown positive results in animal tests, but is no a miracle cure. A Spanish priest treated with ZMapp still died.

The company producing ZMapp warns that stocks are too low to treat large numbers of people. The drug has of yet only been made available to a handful of Western patients.

Meanwhile companies have been promoting more controversial therapies. Nano Silver, a mix of metal silver normally used as a food disinfectant, has been advertised to the governments of countries affected. There is no clear evidence for its effectiveness. In fact, there is strong evidence to suggest it may be dangerous.

The WHO’s decision to allow the immediate use of experimental drugs has both provided a potential cure, but has also exposed many African people to unnecessary harm. Drugs like Nano Silver, which have little chance of undergoing standard clinical trials because of concerns over their safety, are now being tested on Africans. Unsurprisingly these sorts of experimental drugs are very different to ZMapp and other treatments being tried out on Western patients.

The protests

One consequence of this has been uprisings against health workers and aid agencies in the affected countries. Protesters outside the JFK hospital in Monrovia, Liberia, were fired at with live rounds by the military. There have also been protests in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Nigeria.

Why have people turned against those helping? The key factors are failures of local health systems and lack of trust in aid agencies. These have left people afraid to leave their loved ones in isolation centres manned entirely by Western aid workers.

Supportive treatments for Ebola sufferers are not expensive: they include simply keeping patients hydrated. But the lack of resources in the hospitals across the region makes this a very difficult task on a large scale, especially when protective equipment for health workers is unavailable.

This is not just specific to the countries affected by the latest Ebola outbreak. Health Poverty Action calculates that Africa is losing $192bn every year to the rest of the world, as compared to $30bn received in aid.

The current infection is spreading wider and faster than previous ones, partly because people are ignoring public health warnings to keep away from funerals or leave bodies to be buried in designated grave sites. This widespread mistrust is a direct consequence of the financial squeeze on healthcare provision. As one researcher in Sierra Leone and Liberia puts it:

Hospitals in this part of the world have notoriously poor service. Families routinely have to prepare meals and bring them to patients. Families have to go to local pharmacies to buy drugs and even gloves or needles because hospital storerooms are routinely not stocked. People’s apprehensions about the failings of the healthcare system come from experience, not from ignorance.

The profiteers

There is another obstacle: Big Pharma doesn’t have a financial incentive to develop a treatment for Ebola. Until this latest outbreak, even the drugs like ZMapp that stand a chance of working would not have been put out to clinical trial because of the lack of return on costs required to develop them as safe and effective treatments.

Scientists have spoken out about their difficulties in getting potential Ebola drugs into clinical trials. Some of them involved in Ebola research said they were even willing to participate themselves in drug trials.

There is a worrying parallel to the response of health organisations and drugs companies to the rise of AIDS. It took the deaths of thousands before the voices of those affected began to be heard. Grassroots direct action organisations like ACT UP forced governments to listen to HIV positive people. Ebola activists have launched an online petition to demand proper money and research into treatments. Please sign it – and follow their twitter account @AntiEbola for updates.

This is a racist account of the Ebola crisis. Why is it propagating the racist myth that it is uncivilised Africans eating ‘bushmeat’, in itself a racist term, that is the cause of the Ebola spread. How about a proper analysis of the way that African universities were starved of funds and personnel by the neo-liberal policies of the West? And why hasn’t space been given for an African person to make their views known in this article? Why is it always some white person that insists they know how Africans think and behave? Truly, colonialism is not dead!