In part one of our series on the roots of Israeli apartheid, retired history lecturer Neil Rogall looks at the origins of Zionism.

This article is the first in a six-part series on the history of the State of Israel, from the origins of the Zionist movement in Europe to the ethnic cleansing of most of mandatory Palestine in 1948. This history is crucial to understanding the system of apartheid and colonial domination that exists in Palestine today. A full overview of the foundation of the State of Israel can be found in rs21’s pamphlet Israel: the making of a racist state, which can be bought from this website for £4.

The rise of antisemitism in Europe

By the 1880s the majority of the world’s population of nearly 8 million Jews lived in Eastern Europe. Four million of these lived in territories acquired by the Tsarist Empire in the 18th and 19th century. Most were in an area called the “Pale of Settlement” – the only part of the Tsarist empire that Jews were allowed to live without special permits. This stretched from Lithuania on the Baltic to the Black Sea in the south, from Poland in the west to “white Russia” and the Ukraine in the east. All Jewish people faced government restrictions on travel, employment, education and worship.

But there was one Tsarist policy that hit the Jewish communities hardest. This was conscription into the Tsarist armies. The Jewish population had to provide 10 youngsters per thousand population for military service compared to 7 for the non-Jewish population. Even more draconian was that Jews were required to provide conscripts who were between twelve and eighteen years old whereas for the rest of the population it was between eighteen and thirty-five. Military service lasted twenty five years .The Jewish child conscripts were placed in special military establishments where they faced an especially harsh education intended to convert them to Christianity.

By 1888 an official Tsarist government report described the conditions of the Jews as ‘repression and disenfranchisement, discrimination and persecution’.[1]

Of course by this point the Tsarist regime was beginning to face rising discontent. In 1881 the young revolutionaries of Narodnaya Volya (“People’s Will”) assassinated Tsar Alexander. The response of the authorities was to deflect discontent onto the Jewish minority. By the end of that year gangs of peasants and petty criminals organised by the state had attacked over 200 Jewish communities.

Here is a report on one such pogrom in Balta, south Russia during the Jewish Passover in 1882 from a French newspaper Le Temps:

“The riot began in the afternoon; the Jewish inhabitants prepared to defend themselves; whereupon the municipal authorities had them dispersed by troops who beat them with rifle butts. [The following morning], 600 peasants from the surrounding country recommenced the attack and maintained it without further obstacle. It was a scene of pillage, arson, murder and rape to make one tremble with horror…211 were injured, 9 were killed, girls were raped…most houses were demolished”

There were further waves of pogroms whenever Tsarist rule felt threatened, in 1903, after 1905, and after February 1917.

Rise of Nationalism

The latter part of the 19th century saw a rise of competing nationalisms and the creation of nation states in Europe. This was seen most spectacularly in Italy and Germany where unified states were created out of a patchwork of principalities, city-states, and bishoprics.

In eastern and southeast Europe national movements developed demanding independence from their imperial overlords. In the Tsarist Empire there were similar movements amongst the Poles, and the Ukrainians. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire national movements spread amongst the southern Slavs, the Czechs and the Hungarians, as did similar movements in the Balkan provinces of the Ottoman Empire. What became known as “national liberation” was seen as the solution to national oppression – in other words the creation of an independent territorial state for the “oppressed” nation.

The rise of nationalism directed against a ruling power was an act of rebellion against the established authorities. However it could also single out those were not included as ‘part of the nation’. Nationalism often wove together a holy trinity – the unity of people, state, and territory. Therefore minorities defined as “not part of the people” needed to be marginalised or expelled. Of course established states such as Russia could deploy ‘state nationalism’ against the supposed “enemy within” in order to tighten the identification of the population with their rulers

The rise of Zionism

How did Jewish people respond to this dire situation? The vast majority chose emigration where it was feasible. By 1914, two and a half million had fled to the USA. By 1930 this had doubled to five million. Tens of thousands more migrated to South America and Canada, South Africa and Australia. Hundreds of thousands settled in Western Europe, like my own grandparents.

But there were two other responses embraced by a minority of Jews. The first was political radicalism. Large numbers became involved in the struggle against Tsarism. Jews were overrepresented in all wings of the Russian revolutionary movement – populist, anarchist and Marxist. Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky are probably the most well known. In Poland a large Jewish socialist party emerged: the Bund.

The third response was the development of Zionism, a form of Jewish nationalism that believed in establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine, part of the Ottoman Empire. This was a very different sort of movement to that of the revolutionaries.

Theodore Herzl is usually seen as the founding father of Zionism. A journalist from Vienna he was in Paris at the time of the Dreyfus affair. In 1894 a senior French and Jewish army officer was accused falsely of spying for Germany and charged with being a traitor. His case deeply divided France with the French socialist movement playing a prominent part in his defense. Herzl claimed that he was shocked that France, the most liberal society in Europe, home of the “Great Revolution” could harbour such antisemitism.

Herzl, in fact, was already formulating his version of Zionism before the Dreyfus affair. Some historians have argued that Herzl initially believed that Dreyfus was guilty and that his conversion to Zionism because of the racist witch-hunt in France was a myth. But Herzl was not the first to formulate such ideas. Leo Pinsker (1821-91), a Russian Jewish doctor had originally believed that if Jews in Russia won equal rights then antisemitism would disappear. However after the experience of the 1881 pogroms referred to earlier he became convinced that the only way to end “Judeophobia” was to create a Jewish home in Palestine or elsewhere

In his pamphlet Auto-Emancipation he wrote “… to the living the Jew is a corpse, to the native a foreigner, to the homesteader a vagrant, to the proprietary a beggar, to the poor an exploiter and a millionaire, to the patriot a man without a country, for all a hated rival”. [2]

Jews would always suffer from racism because their condition was unnatural and abnormal. Lacking territory, they lacked substance, “like a people [without] a shadow”. [3]

Herzl in his book The Jewish State (1896) reiterated Pinsker’s argument. Antisemitism could only be eradicated if Jews lived alone in their own national state as non-Jews would always be hostile to them.

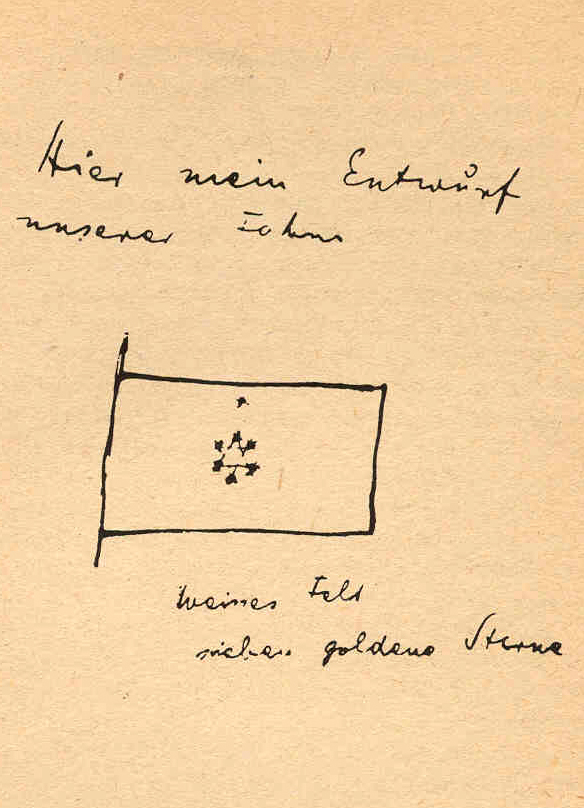

In 1897 the first meeting of Herzl’s World Zionist Organisation took place. Palestine was chosen as the ideal site for a Jewish homeland. This was not because the Zionists were religious. In fact most were atheists.

The Zionists themselves were prejudiced against the Jews of Eastern Europe. They believed they were sunk in a quagmire of illiteracy, backwardness and religious superstition. Only by emigrating and creating a new Jewish-only society could they leave behind the ‘Middle Ages’ and enter the modern age. Here was a doctrine of progress. The fact that many Zionists saw their Zionism as socialist or cooperative is part and parcel of this desire to be modern, influenced as they were by the radical movements in the Russian Empire.

Golda Meir later to be a prime minister of Israel, apparently records that in the 1920s she along with other so called “Labour Zionists” celebrated the great Jewish fast day Yom Kippur with a huge banquet. This was their way of affirming that they had turned a page in Jewish history and that they had thrown the rites, superstitions and legends of their ancestors into the dustbin of history. But all the same the early Zionists chose Palestine because of the resonance the Holy Land would have with ordinary Jews (and Christians) steeped in the Old Testament

In an age where nationalisms were dominant and often hostile to Jewish minorities, it is not surprising that the professionals who dominated the Zionist movement would look for a national solution to their problems. Similarly this was an age of imperialism, and colonial and racist ideas were shared by much of the European middle classes.

The Zionists saw themselves as part of the European colonial project bringing progress to Palestine. This shaped their ideas about the indigenous population – when they talked about a “land without people” this was a standard colonial trope. There were no “civilized” people in Palestine; there were no “improving” farmers with a claim to the land.

But they did know the land was inhabited. Here is Moshe Smilansky, a Zionist farmer’s leader writing in 1914:

“We must not forget that we are dealing here with a semi-savage people, which has extremely primitive concepts. And this is his nature: If he senses in you power – he will submit and will hide his hatred for you. And if he senses weakness – he will dominate you…owing to the many tourists and urban Christians, there developed among the Arabs base values which are not common among other primitive people…to lie, to cheat, to harbour grave unfounded suspicions and to tell tales…and a hidden hatred for the Jews.”

Ben-Gurion, the future founder of Israel writing in 1906 uses a different colonial cliché:

“They [the Palestinian Arabs] make a very good impression. They are nearly all good-hearted and are easily befriended. One might say they are like big children”.

But irrespective of how they spoke about the Palestinians they knew what obstacle the Zionist project faced. Here is Smilansky again:

“Either the Land of Israel belongs in the national sense to those Arabs who settled there in recent times, and then we have no place there and we must say explicitly: The land of our fathers is lost to us [Or] if the land of Israel belongs to us, to the Jewish people, then our national interests come before all else…it is not possible for one country to serve as the homeland for two peoples.” [4]

One further factor spurred on the Zionists efforts. As a result of the murderous pogroms in Eastern Europe, thousands of refugees were flocking to Western Europe. These poor, ill-educated, religious refugees were very different to the assimilated Western European Jews. The latter were often deeply hostile to their co-religionists, fearing they would stir-up antisemitism and make life more difficult for them. It would they thought, be so much better if these eastern Jews were to emigrate to Palestine and leave them in peace.

How were the Zionists to achieve their aims? There were two basic approaches. The first influenced by Pinsker was to emigrate quietly to Palestine and hope by stealth to create a Jewish society. So by the end of the 19th century there were 21 Jewish settlements with about 4,500 inhabitants, but by 1914 this was 85,000.

The second and ultimately successful strategy was that of Herzl and his “political Zionism”. Here is Avi Shlaim writing in The Iron Wall:

“His most persistent efforts were directed at persuading the Ottoman Sultan to grant a charter for Jewish settlement and a Jewish Homeland in Palestine. But he also approached many other world leaders and influential magnates for help in promoting his pet project. Amongst those who granted him an audience, were the Pope, the King of Italy, the German Kaiser and Joseph Chamberlain, the British colonial secretary. In each case Herzl presented his project in a manner best calculated to appeal to the listener: to the Sultan he promised Jewish capital, to the Kaiser he intimated that the Jewish territory would be an outpost of Berlin, to Chamberlain he held out the prospect that the Jewish territory would be a colony of the British Empire.”

In the end it was to be British support that led to the initial success of the Zionist project. The reasons behind this will be the subject of my next piece.

Part 2: Palestine, the Great War and British imperialism

References

1. Benny Morris, Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist Arab Conflict 1881-1999

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leon_Pinsker

3. Benny Morris, Righteous Victims

4. Benny Morris, Righteous Victims

The third part is here

http://rs21.org.uk/2014/09/04/the-origins-of-the-iron-wall-zionist-settlers-during-the-mandate/

The second part is now available here: http://rs21.org.uk/2014/08/28/palestine-the-great-war-and-british-imperialism/

Reblogged this on ΕΝΙΑΙΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ ΠΑΙΔΕΙΑΣ.